Book Review: 137 — Jung, Pauli and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession

Jung, Pauli, and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession

by Arthur I. Miller

Back in grad school, I first learned of the Fine Structure Constant when a physics prof casually mentioned how some scientists find mystical significance in it. That was a curious thing to mention in a grad-level electromagnetism course, I thought to myself. Later I read what the famous physicist Richard Feynman had to say about this scientific constant, that “all good theoretical physicists put this number up on their wall and worry about it.” Hmmm, what the hell is this thing? After years of science and math education, I’d learned to be skeptical of mystical numerology (don’t get me started on the movie “Pi”). But here I was, grad student in physics, being told smart people are thinking deep thoughts about this grandiose number called the Fine Structure Constant. What the hell is all this about?

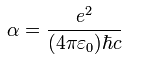

So what is it? It’s what scientists call a “constant” — a number that pops up in an equation or expression for some scientific concept. There are lots of them, and if you took a physics class at any point, you learned several of them. There’s “G”, the gravitational constant. There’s “e0“, a constant that pops up in the equations of electromagnetism. Maybe the most famous one of all is “c”, the speed of light. The Fine Structure Constant is yet another constant that happens to be a combination of a few other constants — it’s the electric charge squared, divided by this mess: 4 * pi * the electric constant * Planck’s constant * the speed of light. It first popped up in early quantum mechanics, and has been bedeviling physicists ever since. Here it is in all its mathematical glory:  What makes it so cool? After all, numerical constants pop up everywhere — this particular constant contains four other physics constants, plus the all-star number pi. Why do physicists get their panties in a mobius strip over this number? Well, for one, it pops up in multiple places in quantum theory. For another, it happens to combine a lot of other constants important in physics – combining the speed of light (which is gargantuan) with Planck’s constant (which relates to the very very small) for example, is something you don’t come across every day. For yet another, it’s dimensionless. That means it’s a pure number, devoid of any units like “meters” or “hectares”. Other numerical constants will change their value depending on what units you prefer. The speed of light, for example, is 3 x 108 if you prefer meters per second, but is 9.46 x 1026 if you’d rather measure your speed in angstroms per decade. This particular constant is the same numerical value no matter what unit system you’re using, since it has no units — it’s a naked unadulterated number, without any units whatsoever. That promotes it to the upper echelons of numbers like pi — pure numbers important to the foundations of physical law, numbers that are the same no matter what alien civilization measures them anywhere across the universe — it’s approximately 1/137, no matter whether you prefer metric or avoirdupois, or whether you’re human or Wookiee. So it’s a number that physicists pay particular attention to.1

What makes it so cool? After all, numerical constants pop up everywhere — this particular constant contains four other physics constants, plus the all-star number pi. Why do physicists get their panties in a mobius strip over this number? Well, for one, it pops up in multiple places in quantum theory. For another, it happens to combine a lot of other constants important in physics – combining the speed of light (which is gargantuan) with Planck’s constant (which relates to the very very small) for example, is something you don’t come across every day. For yet another, it’s dimensionless. That means it’s a pure number, devoid of any units like “meters” or “hectares”. Other numerical constants will change their value depending on what units you prefer. The speed of light, for example, is 3 x 108 if you prefer meters per second, but is 9.46 x 1026 if you’d rather measure your speed in angstroms per decade. This particular constant is the same numerical value no matter what unit system you’re using, since it has no units — it’s a naked unadulterated number, without any units whatsoever. That promotes it to the upper echelons of numbers like pi — pure numbers important to the foundations of physical law, numbers that are the same no matter what alien civilization measures them anywhere across the universe — it’s approximately 1/137, no matter whether you prefer metric or avoirdupois, or whether you’re human or Wookiee. So it’s a number that physicists pay particular attention to.1

So let’s get to this book, a history of the lifelong friendship and collaboration between the eminent scientists Wolfgang Pauli (the famous physicist) and Carl Jung (the famous psychoanalyst). On one level this book serves as an in-depth but entertaining biography of both of these important men in science, particularly Pauli. On another level, it kinda sorta covers the fascinating relationship between the two. So if you’re looking for biographies of Pauli and Jung, but can’t be bothered to lug two separate books around, this one’s for you. Many chapters focus entirely on only one of the two, leaving the other sadly neglected — it’s almost as if someone shuffled the chapters of two separate biographies together. The history of their actual interactions is much more sparse, likely because these men kept the details of their lifelong friendship and collaboration to themselves. The book transitions abruptly between highly-polished individual biographies to quite speculative musings on their relationship. Of course we may never know what really happened between these two brilliant men, but it makes for a rocky historical narrative

As a physicist, I found this book especially valuable to read about Pauli, a luminary I only knew until now from various discoveries and theorems that bear his name. (Pauli is most famous for his exclusion principle, but he also predicted the existence of the famously aloof particle the neutrino, was one of the premier architects of quantum theory, and later contributed to renormalization.) I was impressed with the scientific meat Miller included to the biography of Pauli, which made me feel slightly better about how lost I felt in the alternating chapters that focused on Jung — a reader who is my equivalent in psychology will probably find much of the physics goes over their heads. You might need to be well-versed in both disciplines to really appreciate the biographies of both men equally.

Nevertheless, this book was a bit disappointing, and not just because we only get an imperfect view of their relationship (from this book or indeed from any source whatsoever). My disappointment stems from the lack of discussion about the goddamn fine structure constant, the scientific constant that is literally the first word in the title of the book. Yes, it is an important number in science, one that is poorly understood and rates as practically mystical for more than one luminary of physics. Then why does this book barely mention it until we’re 80% of the way through the book? Yes, that’s right — we don’t learn about the fine structure constant until the last chapter. It’s an unquestionably important number, easily deserving of a book-length treatment, so why isn’t it discussed until nearly the end of the book?

Personally, I think the cult that has grown around the fine structure constant is overrated. While I won’t second-guess those hard-nosed physicists who worry about it (like the famously practical-minded Richard Feynman), I do find myself with a healthy degree of skepticism regarding the fine structure constant as some mystical kabbalistic number. Complaint numero uno: those who read up about this constant will find a lot of noise about the integer 137 (such as that it’s prime, or supposedly appears in the Kabbalah). But the actual number that appears in the scientific theories isn’t the integer 137 –it’s been measured to be about 137.035999074. That’s close to 137, but hell, the number pi is close to the integer 3, and nobody ever asserts that pi = 3 (aside from some perhaps-apocryphal state legislature somewhere). You’d think that a religion built around a mystical number wouldn’t have to round down to the nearest integer.

Complaint numero two: there is plenty of mystical numerology for discussion in the relationship between Jung and Pauli, so why give the ol’ bait and switch with 137? I suspect the dirty little secret is that even Pauli and Jung weren’t so obsessed with 137 as they were other “mystical” numbers, and that this is reflected in the lack of attention given to 137 in this book — in fact, most of the book centers on the perhaps more reasonable mystical numbers 3 and 4. These are numbers much more intimately related to our everyday lives, and have been symbolic in religions and philosophies for centuries. One of Pauli’s key contributions to science was the discovery of a fourth “quantum number”, which in his eyes (potentially) may have reflected an ancient symbolic progression from the fundamental number 3 to 4. While I have my skepticism whether Pauli’s discovery of four quantum numbers really has anything to do with the symbolic archetypes of the numbers 3 and 4 in our collective psychology, I’m fascinated to read about how they tried to make the connection. Their obsession with these two integers is the more honest depiction of their collaboration than the fine structure constant, and in itself is easily worthy of a full book. Why conflate it with all the other mystical musings around the fine structure constant? (As for the story of the fine structure constant itself, maybe I’ll save that for another blog article someday.)

Readers interested in the connections between hard-nosed science and more ethereal symbolism may really enjoy this book (though the more educated of those readers will already be aware of the collaboration between these two). And there’s much to be fascinated about – the fact that a pillar of science like Pauli took this stuff seriously should make other hard-nosed skeptics in the science community pause before they dismiss it as fantasy. Yes, there may not have ultimately been much that resulted from their collaboration, but if Pauli thought it worthy of his time, shouldn’t the rest of us as well? But this book does itself no service with the fine structure constant bait-and-switch, perhaps unintentionally giving ammunition to those who would scoff at a deep connection between theoretical physics and psychology. For those of us who believe there is something fundamental in common between physical sciences and humanities, this book (like many others) doesn’t quite do the connection justice.

Footnotes:

1. You might be wondering why being unitless is such a big deal. After all, I could cook up any number of numerical abominations that combine other unit-laden scientific constants, where all the units cancel. Wouldn’t I then wind up with another unitless constant, that people should worship as a kabbalistic mystical mystery? Yes, but it likely isn’t useful in any scientific description of the world. The fine structure constant has popped up in multiple places in various scientific theories, and so it is 1) unitless, and 2) descriptive of our universe. That’s what makes physicists go ga-ga over it.

Follow Timeblimp on Twitter

Follow Timeblimp on Twitter